Click here to read my full interview with Ximena Sariñana on Remezcla.

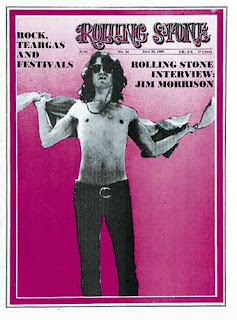

defined and revolutionized rock & roll as a legitimate genre to be taken seriously, furthermore than the youth rebel’s and counterculture’s music. Draper declares, “Instead of defining rock & roll, or deifying it, Rolling Stone covered it – a truly revolutionary idea. Its writers interviewed Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Mick Jagger, Janis Joplin, Pete Townshend and Eric Clapton with the sense of purpose a Time reporter would bring to an interview with Henry Kissinger. Musicians were worthy news figures, proclaimed Rolling Stone, and their music was worthy of analysis” (1990, 8). From its featured stories, questions and answers, breaking news, presidential scandal stories, special editions, music and movie previews, and revolutionary covers, have all served a purpose in keeping RS at the forefront of music lovers’ top list.

defined and revolutionized rock & roll as a legitimate genre to be taken seriously, furthermore than the youth rebel’s and counterculture’s music. Draper declares, “Instead of defining rock & roll, or deifying it, Rolling Stone covered it – a truly revolutionary idea. Its writers interviewed Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Mick Jagger, Janis Joplin, Pete Townshend and Eric Clapton with the sense of purpose a Time reporter would bring to an interview with Henry Kissinger. Musicians were worthy news figures, proclaimed Rolling Stone, and their music was worthy of analysis” (1990, 8). From its featured stories, questions and answers, breaking news, presidential scandal stories, special editions, music and movie previews, and revolutionary covers, have all served a purpose in keeping RS at the forefront of music lovers’ top list.  about establishing a medium that represented the youth culture, or entrepreneurship, than to protesting on campus grounds. One acquaintance of Wenner at that time even said that his main reason for developing RS was that so he could meet his hero, John Lennon (34). Despite of this being true or not, RS became much more than a magazine about celebrity or rock musician gossip or even simple platonic visions of music with hardly any meaning, but a cultural force which captured the counterculture for what it really was, a legitimate expression of why these youths were so captivated by rock & roll, and a voice to these rock icons who ‘authentically’ express themselves and what the meaning of music had to them, and its audiences. Consequently, Wenner dropped out of UC, Berkeley and went on becoming the co-founder, publisher, and editor of RS in October of 1967, along with the other co-founder, Ralph Gleason. All it took was collecting $7,500, and the printing press begun to roll.

about establishing a medium that represented the youth culture, or entrepreneurship, than to protesting on campus grounds. One acquaintance of Wenner at that time even said that his main reason for developing RS was that so he could meet his hero, John Lennon (34). Despite of this being true or not, RS became much more than a magazine about celebrity or rock musician gossip or even simple platonic visions of music with hardly any meaning, but a cultural force which captured the counterculture for what it really was, a legitimate expression of why these youths were so captivated by rock & roll, and a voice to these rock icons who ‘authentically’ express themselves and what the meaning of music had to them, and its audiences. Consequently, Wenner dropped out of UC, Berkeley and went on becoming the co-founder, publisher, and editor of RS in October of 1967, along with the other co-founder, Ralph Gleason. All it took was collecting $7,500, and the printing press begun to roll.  Even though the first issue of RS is not necessarily one of the most memorable covers, it sets the platform for the rest of the issues to come in terms of their style. As stated before, Jann Wenner did in fact idolize John Lennon. After gathering the RS staff and preparing all other aspects for the launching of the first issue, Wenner had written a review of John Lennon’s film ‘How I Won the War.’ A still shot of Lennon in this film would en up setting the front page cover.

Even though the first issue of RS is not necessarily one of the most memorable covers, it sets the platform for the rest of the issues to come in terms of their style. As stated before, Jann Wenner did in fact idolize John Lennon. After gathering the RS staff and preparing all other aspects for the launching of the first issue, Wenner had written a review of John Lennon’s film ‘How I Won the War.’ A still shot of Lennon in this film would en up setting the front page cover.

clarifies that not only musicians were the muses or those worthy to make the cover. However, there have been moments of high coverage about certain extreme conservative political groups, peaks of spirituality, and mad and cynical situations. As RS has interviews with some of the most incredible, crazy, and mad people, it grants to look in deeper than what official outlets of communication would report. It strives to look inside the mind of the individuals and why they make the decisions they make.

clarifies that not only musicians were the muses or those worthy to make the cover. However, there have been moments of high coverage about certain extreme conservative political groups, peaks of spirituality, and mad and cynical situations. As RS has interviews with some of the most incredible, crazy, and mad people, it grants to look in deeper than what official outlets of communication would report. It strives to look inside the mind of the individuals and why they make the decisions they make.  Because the obsession with murders, killings, riots and death were a huge aspect of what consumers were buying, these next three issues below also proved to be big sellers. Wenner states, Wenner states, “Another of our early lessons in publishing was that death sells. When Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix died within weeks of each

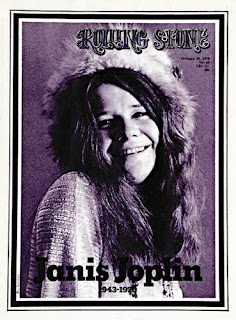

Because the obsession with murders, killings, riots and death were a huge aspect of what consumers were buying, these next three issues below also proved to be big sellers. Wenner states, Wenner states, “Another of our early lessons in publishing was that death sells. When Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix died within weeks of each  other, our staff placed simple, classic portraits on the cover, with type stating just the artist’s name and dates of birth and death. There was nothing more to say” (2006, 8).

other, our staff placed simple, classic portraits on the cover, with type stating just the artist’s name and dates of birth and death. There was nothing more to say” (2006, 8).

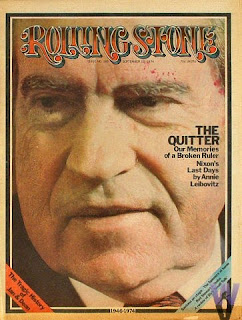

Another ongoing series of publications in RS would stress former president, Richard Nixon. Draper highlights again another dimension into the transitory decade of 60s to 70s. Then “Came a crooked President and a crooked new decade, and Rolling Stone stopped talking about love and revolution. New Morality met head-on with New Reality. From 1970 until 1977, no magazine in America was as honest or as imaginative…Greater truths were its aim…from Nixon, the FBI and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to Woodstock, Charles Manson and the Symbionese Liberation Army” (Draper: 1990, 7). So as this whole spotlight of cynical individuals was featured in RS, it was subsequently what was being favored in America, in terms of consuming the spectacle.

Another ongoing series of publications in RS would stress former president, Richard Nixon. Draper highlights again another dimension into the transitory decade of 60s to 70s. Then “Came a crooked President and a crooked new decade, and Rolling Stone stopped talking about love and revolution. New Morality met head-on with New Reality. From 1970 until 1977, no magazine in America was as honest or as imaginative…Greater truths were its aim…from Nixon, the FBI and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to Woodstock, Charles Manson and the Symbionese Liberation Army” (Draper: 1990, 7). So as this whole spotlight of cynical individuals was featured in RS, it was subsequently what was being favored in America, in terms of consuming the spectacle.

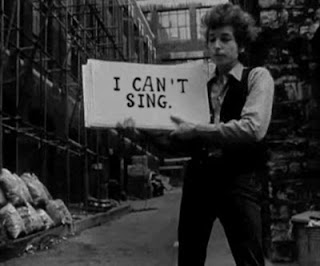

naturally came to look and review this one. As those who have read my previous posts, it is quite obvious that I am intrigued with Bob Dylan. Either if it was analyzing him in the context of authenticity, or weather it was speaking of him in the context of the folk revival and counterculture. I therefore wanted to take a look at this film again and view him from the various transitions he underwent publicly and relate it to the milieu of that given time. Haynes highlights this extremely well.

naturally came to look and review this one. As those who have read my previous posts, it is quite obvious that I am intrigued with Bob Dylan. Either if it was analyzing him in the context of authenticity, or weather it was speaking of him in the context of the folk revival and counterculture. I therefore wanted to take a look at this film again and view him from the various transitions he underwent publicly and relate it to the milieu of that given time. Haynes highlights this extremely well. career, he has maintained the attention of popular culture (however not under tabloid gossip) and loyal and new following throughout the years. I guess I am just fascinated by his chameleonic personifications that he, maybe intentionally or not, put out into the public sphere. To some extent, this revealed him from being ahead of his own time, and for the rest of us who did notice, this sort of gave him some prophetic attributes.

career, he has maintained the attention of popular culture (however not under tabloid gossip) and loyal and new following throughout the years. I guess I am just fascinated by his chameleonic personifications that he, maybe intentionally or not, put out into the public sphere. To some extent, this revealed him from being ahead of his own time, and for the rest of us who did notice, this sort of gave him some prophetic attributes. display concept driven representations which are full of symbolism. This can also be explained as how he challenges the work of Rimbaud as a poet which also mirrors him. Arthur’s role gives meaning to the insatiable and uncontainable energy displayed in the rest of the characters. It gives direction to these transitions.

display concept driven representations which are full of symbolism. This can also be explained as how he challenges the work of Rimbaud as a poet which also mirrors him. Arthur’s role gives meaning to the insatiable and uncontainable energy displayed in the rest of the characters. It gives direction to these transitions. of his origins which resembled an ideology of Guthrie’s, politically leftist and the attitude of a vagabond. The fact that “Woodie” was played by a young African American boy already incorporates the fabrication embedded in this character’s persona; it was like the elephant in the room. He manufactured stories like traveling and performing with a circus family and being brought up by many foster parents. However, he did sprinkle some truth here and there, like saying he lived in Hibbing, Minnesota, though he was actually born and raised there (that is the real life Dylan). Woodie’s selection of songs are old traditional songs outside his time. He is given a valuable suggestion to sing songs about his own time.

of his origins which resembled an ideology of Guthrie’s, politically leftist and the attitude of a vagabond. The fact that “Woodie” was played by a young African American boy already incorporates the fabrication embedded in this character’s persona; it was like the elephant in the room. He manufactured stories like traveling and performing with a circus family and being brought up by many foster parents. However, he did sprinkle some truth here and there, like saying he lived in Hibbing, Minnesota, though he was actually born and raised there (that is the real life Dylan). Woodie’s selection of songs are old traditional songs outside his time. He is given a valuable suggestion to sing songs about his own time.  depicts a PBS documentary style narrative with the reconstruction of “classic” still photographs and interviews of Alice Fabian who represents Joan Baez among others. The part of Rollins simulates the documentary by Martin Scorsese’, No Direction Home. We see how Rollins takes on a political mantle by singing songs in traditional form with contemporary concerns. Like in real life, this form of singing distinguished Rollin from the rest of his contemporaries who largely sung recollections of old, topical songs.

depicts a PBS documentary style narrative with the reconstruction of “classic” still photographs and interviews of Alice Fabian who represents Joan Baez among others. The part of Rollins simulates the documentary by Martin Scorsese’, No Direction Home. We see how Rollins takes on a political mantle by singing songs in traditional form with contemporary concerns. Like in real life, this form of singing distinguished Rollin from the rest of his contemporaries who largely sung recollections of old, topical songs.  actor within of the film within the film as Jack Rollins. His passion for wife Claire and infidelity are also a focus. Claire represents a mixture of Dylan’s two famous leading ladies. They are Suze Rotolo, who comes out on the cover of Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (Claire is an abstract painter like Suze), but more evidently, Dylan’s first wife Sara Lownds, who were married for several years and had children together. Another Dylan character is Billy the Kid, representing when he hid away from the public sphere.

actor within of the film within the film as Jack Rollins. His passion for wife Claire and infidelity are also a focus. Claire represents a mixture of Dylan’s two famous leading ladies. They are Suze Rotolo, who comes out on the cover of Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (Claire is an abstract painter like Suze), but more evidently, Dylan’s first wife Sara Lownds, who were married for several years and had children together. Another Dylan character is Billy the Kid, representing when he hid away from the public sphere. “Positively 4th Street.” His music had moved into this surreal landscape where urban sensibilities were clashing with the reminiscing sentiments of the folk era. There was also a great sense of surrealism and the obscured of popular culture collapsing onto intellectual and high culture. These new perceptions were evidently seen with the Beatniks, Allen Ginsburg, and Andy Warhol. A high modernist “surreality” was consequently reflected in the music of both Dylan, and the character Jude, during 1965 and 1966.

“Positively 4th Street.” His music had moved into this surreal landscape where urban sensibilities were clashing with the reminiscing sentiments of the folk era. There was also a great sense of surrealism and the obscured of popular culture collapsing onto intellectual and high culture. These new perceptions were evidently seen with the Beatniks, Allen Ginsburg, and Andy Warhol. A high modernist “surreality” was consequently reflected in the music of both Dylan, and the character Jude, during 1965 and 1966.  from. It was the force of being pinned down and of being asked to explain himself. It became a series of conflicts and show downs between Quinn and the press. Possibly his fear of being unmasked, and being asked what his intent as an artist suggested. Maybe a kind of intentionality that is close to the idea of being deceitful or being artificial, and to close to the idea of being reviled. Quinn bristles against all of this. He later is revealed as Aaron Jacob Edelstein, like the real Bob Dylan is revealed as Robert Zimmerman, both revelations as suburban, middle class, conventional characters. The fact is that both Quinn and Dylan are those who see a ‘truth’ of I may call it, in ways that nobody else is capable of. Furthermore and ultimately, they are those who refuse to be hurt and be put into a place of vulnerability. They refuse to be put in a place of being asked to define or defend their work or music. Dylan and Quinn are both surprisingly defensive, especially for someone who is in control of their creative abilities, and someone who intimidated the Beatles and Andy Warhol and is on the very top of their cultural game. As a whole, “Ballad of a Thin Man” represents the figure of the establishment, or that which the mass media forces to give any prescribed definitions to; any subject faces the danger of being represented as deceitful or sensational. This song is highly dramatized in the film. Quinn refused to be prescribed in any platform.

from. It was the force of being pinned down and of being asked to explain himself. It became a series of conflicts and show downs between Quinn and the press. Possibly his fear of being unmasked, and being asked what his intent as an artist suggested. Maybe a kind of intentionality that is close to the idea of being deceitful or being artificial, and to close to the idea of being reviled. Quinn bristles against all of this. He later is revealed as Aaron Jacob Edelstein, like the real Bob Dylan is revealed as Robert Zimmerman, both revelations as suburban, middle class, conventional characters. The fact is that both Quinn and Dylan are those who see a ‘truth’ of I may call it, in ways that nobody else is capable of. Furthermore and ultimately, they are those who refuse to be hurt and be put into a place of vulnerability. They refuse to be put in a place of being asked to define or defend their work or music. Dylan and Quinn are both surprisingly defensive, especially for someone who is in control of their creative abilities, and someone who intimidated the Beatles and Andy Warhol and is on the very top of their cultural game. As a whole, “Ballad of a Thin Man” represents the figure of the establishment, or that which the mass media forces to give any prescribed definitions to; any subject faces the danger of being represented as deceitful or sensational. This song is highly dramatized in the film. Quinn refused to be prescribed in any platform.

Raised in Iowa by a family of musicians, David Schroeder was musically cultivated ever since a young age. As the youngest of six boys, he was exposed to and inspired by what his father played from his record collection, as well as the musical programming he saw and heard on TV and radio. When it was time for him to learn an instrument, Schroeder inherited a saxophone from one of his older brothers. He says, “Coincidentally, I was given the saxophone and that happened to be a jazz instrument. That led me to get very interested in jazz.” Schroeder explains that everyone in his surroundings was going into music school, and evidently he did too since his tender days in grade school. It was as if he was destined to be a jazz musician.

Raised in Iowa by a family of musicians, David Schroeder was musically cultivated ever since a young age. As the youngest of six boys, he was exposed to and inspired by what his father played from his record collection, as well as the musical programming he saw and heard on TV and radio. When it was time for him to learn an instrument, Schroeder inherited a saxophone from one of his older brothers. He says, “Coincidentally, I was given the saxophone and that happened to be a jazz instrument. That led me to get very interested in jazz.” Schroeder explains that everyone in his surroundings was going into music school, and evidently he did too since his tender days in grade school. It was as if he was destined to be a jazz musician.  In the United States, the folk revival represented a movement that gave a voice to the younger generation during the palpable social and political transitions of the time. It was the rise of a countercultural movement which took on the musical folkloric traditions of the time when the US was facing economical turmoil. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a working class folk singer by the name of Woody Guthrie wrote realms of simple yet prevailing songs that vividly detailed the American experience. From Guthrie came the idea that songs could carry hard-hitting messages of social and political protest. A decade after, Pete Seeger, the Harvard college journalist student dropout, also projected a leftist ideology with songs of protest with his banjo.

In the United States, the folk revival represented a movement that gave a voice to the younger generation during the palpable social and political transitions of the time. It was the rise of a countercultural movement which took on the musical folkloric traditions of the time when the US was facing economical turmoil. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a working class folk singer by the name of Woody Guthrie wrote realms of simple yet prevailing songs that vividly detailed the American experience. From Guthrie came the idea that songs could carry hard-hitting messages of social and political protest. A decade after, Pete Seeger, the Harvard college journalist student dropout, also projected a leftist ideology with songs of protest with his banjo. wears a t-shirt that says “Corporate Magazines Still Suck”. Boorstin points out about the transition from heroes shifting to celebrities in magazines: “Studies of biographies in popular magazines suggest that editors, and supposedly also readers, of such magazines not long ago shifted their attention away from the old-fashioned hero. From the person known form some serious achievement, they have turned their biographical interests to the new-fashioned celebrity” (59). Barker and Taylor commented on Kurt’s choice of t-shirt by stating he “castigated himself publicly for selling out while continuing to strive for further success.” Furthermore, Barker and Taylor quote Cobain: “I don’t blame the average 17-year-old punk-rock kid for calling me a sellout. I understand that. Maybe when they grow up a little bit, they’ll realize there’s more things to life than living out your rock & roll identity so righteously” (4).

wears a t-shirt that says “Corporate Magazines Still Suck”. Boorstin points out about the transition from heroes shifting to celebrities in magazines: “Studies of biographies in popular magazines suggest that editors, and supposedly also readers, of such magazines not long ago shifted their attention away from the old-fashioned hero. From the person known form some serious achievement, they have turned their biographical interests to the new-fashioned celebrity” (59). Barker and Taylor commented on Kurt’s choice of t-shirt by stating he “castigated himself publicly for selling out while continuing to strive for further success.” Furthermore, Barker and Taylor quote Cobain: “I don’t blame the average 17-year-old punk-rock kid for calling me a sellout. I understand that. Maybe when they grow up a little bit, they’ll realize there’s more things to life than living out your rock & roll identity so righteously” (4). “Kurt Cobain first approached music as a fan…Many of his attitudes came from observing how his musical heroes saw the world and wanting to emulate them…When he became a successful performer himself he knew well how the fans felt about him, the demands they would make, and the emotional connection they had with him. He knew that above all, his fans expected him to keep it real and to not forget where he had come from” (19).

“Kurt Cobain first approached music as a fan…Many of his attitudes came from observing how his musical heroes saw the world and wanting to emulate them…When he became a successful performer himself he knew well how the fans felt about him, the demands they would make, and the emotional connection they had with him. He knew that above all, his fans expected him to keep it real and to not forget where he had come from” (19). approach on the notion of authenticity, but empathetic to the 17-year-old punk rock garage kid, who he justified himself to, as being real and honest. Just like Cobain expected for his personal heroes as a kid.

approach on the notion of authenticity, but empathetic to the 17-year-old punk rock garage kid, who he justified himself to, as being real and honest. Just like Cobain expected for his personal heroes as a kid.

section that keep the music tight and solid. As Dave humorously encourages kids to "Not smoke cigarettes or become musicians," all in good fun of drinking whiskey and staying up till the morning, the Party Death’s music is gritty, loud, with a solid hard, and bluesy base. Like in the words of Jack, "We're a fuckin' dirty and hard rock 'n' roll band", and that's how it should be.

section that keep the music tight and solid. As Dave humorously encourages kids to "Not smoke cigarettes or become musicians," all in good fun of drinking whiskey and staying up till the morning, the Party Death’s music is gritty, loud, with a solid hard, and bluesy base. Like in the words of Jack, "We're a fuckin' dirty and hard rock 'n' roll band", and that's how it should be.

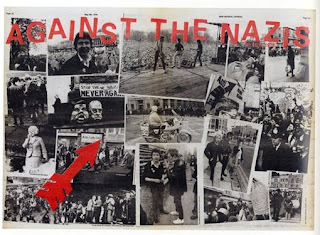

most remembered yet atrocious acts in Southall, UK. Other Prominent bands arousing from the racist tensions were roots and dub reggae artists like Misty in Roots, Linton Kwesi Johnson, and Steel Pulse among others. Though punk and reggae by ideological social expressions seem to be oppositional with one another -- sound-wise, reggae carries the steady off-beat syncopation of harmonious sounds with lyrical content of one love and unity, while punk projects the raucous power-chord dissonance of anti-establishment attitude and rebelliousness -- what's important to get across are the effects of reggae and punk musicians producing a counter-narrative to the dominant discourses that shape violence, oppressions and injustices of acts of racism in marginal sectors.

most remembered yet atrocious acts in Southall, UK. Other Prominent bands arousing from the racist tensions were roots and dub reggae artists like Misty in Roots, Linton Kwesi Johnson, and Steel Pulse among others. Though punk and reggae by ideological social expressions seem to be oppositional with one another -- sound-wise, reggae carries the steady off-beat syncopation of harmonious sounds with lyrical content of one love and unity, while punk projects the raucous power-chord dissonance of anti-establishment attitude and rebelliousness -- what's important to get across are the effects of reggae and punk musicians producing a counter-narrative to the dominant discourses that shape violence, oppressions and injustices of acts of racism in marginal sectors.  of black people, self-victimizing the whites, and that immigration of colored people was problematic for most of the UK’s troubles. Throughout the demonstrations, police authorities -- many of them on their horses and vans -- began vigorously interfering with protester and violently shoving and hitting them with their rods. Police's actions caused a massive riot amongst protesters. Within this, a young teacher by the name of Blair Peach was hit in the head by police, and consequently led to his death. This New Zealand native and leader of the Anti-Nazi League unfortunately gave his life for the struggle of human rights and equality. A decade after, Punjabi teenager Kuldip Singh Sekhon was also murdered by racism in Southall. Similarly, on April 22, 1993, 18-year-old black British Stephen Lawrence was stabbed to death while waiting for a bus in South East London. These sparked massive responses from the Southall community and further out.

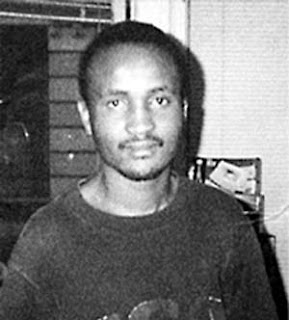

of black people, self-victimizing the whites, and that immigration of colored people was problematic for most of the UK’s troubles. Throughout the demonstrations, police authorities -- many of them on their horses and vans -- began vigorously interfering with protester and violently shoving and hitting them with their rods. Police's actions caused a massive riot amongst protesters. Within this, a young teacher by the name of Blair Peach was hit in the head by police, and consequently led to his death. This New Zealand native and leader of the Anti-Nazi League unfortunately gave his life for the struggle of human rights and equality. A decade after, Punjabi teenager Kuldip Singh Sekhon was also murdered by racism in Southall. Similarly, on April 22, 1993, 18-year-old black British Stephen Lawrence was stabbed to death while waiting for a bus in South East London. These sparked massive responses from the Southall community and further out.  about to be gone. After returning from a meal, Diallo was standing outside a building in the Bronx when four civilian dressed white police officers approached him. The officers claimed they had confused him for a serial rapist. The officers claim they shouted they were the NYPD and demanded for Diallo to freeze with his hands up. The young man frightens and runs up his building. While all police officers are chasing him, Amadou reaches for his pocket to pull out his wallet which cost him his life. One police officer falls to the floor by accident and consequently, another shouts “Gun!” This catastrophe ends up as a rampage shooting Diallo an exaggerated amount of forty-one times.

about to be gone. After returning from a meal, Diallo was standing outside a building in the Bronx when four civilian dressed white police officers approached him. The officers claimed they had confused him for a serial rapist. The officers claim they shouted they were the NYPD and demanded for Diallo to freeze with his hands up. The young man frightens and runs up his building. While all police officers are chasing him, Amadou reaches for his pocket to pull out his wallet which cost him his life. One police officer falls to the floor by accident and consequently, another shouts “Gun!” This catastrophe ends up as a rampage shooting Diallo an exaggerated amount of forty-one times.

Makeda “Dread” Cheatom, known as San Diego’s “most colorful flower child,” is an ambassador of art and activism. "She has worked tirelessly to promote peace, love, culture (and counterculture), art, music and humanity via the WorldBeat Cultural Center, Radio Fusion Reggae Makossa Show, Bob Marley Day, as well as her many other projects and causes. Since 1976, she has been on a mindful, multi-cultural mission to make the world a better place. From opening The Prophet, San Diego’s first non-smoking vegetarian restaurant (irking at least one visiting smoker in the process, ex-Beatle George Harrison), to befriending Bob Marley and Fidel Castro; from pioneering California’s longest running reggae radio show 91X, to spreading the WorldBeat word of positivity and unity, Ms. Dread has been an active altruist."

Makeda “Dread” Cheatom, known as San Diego’s “most colorful flower child,” is an ambassador of art and activism. "She has worked tirelessly to promote peace, love, culture (and counterculture), art, music and humanity via the WorldBeat Cultural Center, Radio Fusion Reggae Makossa Show, Bob Marley Day, as well as her many other projects and causes. Since 1976, she has been on a mindful, multi-cultural mission to make the world a better place. From opening The Prophet, San Diego’s first non-smoking vegetarian restaurant (irking at least one visiting smoker in the process, ex-Beatle George Harrison), to befriending Bob Marley and Fidel Castro; from pioneering California’s longest running reggae radio show 91X, to spreading the WorldBeat word of positivity and unity, Ms. Dread has been an active altruist."  happening around us, as well as where our food is coming from, how it is made, and by whom; considering migrant farm workers, rising levels of hormone injected animals, and the conglomerate corporations profiting from it. Through email blasts and online blogs, Makeda’s message for her fast went out to thousands of individuals worldwide. Hundreds of individuals have responded in locations from Japan, Ghana, Brazil, Mexico, U.S. and other parts of the world showing her companionship and giving her thanks especially in difficult times all over the world. They are now jumping in the fasting bandwagon! Makeda Dread continues her mission of spreading love, positivity, health and the amalgamation and appreciation of all cultures.

happening around us, as well as where our food is coming from, how it is made, and by whom; considering migrant farm workers, rising levels of hormone injected animals, and the conglomerate corporations profiting from it. Through email blasts and online blogs, Makeda’s message for her fast went out to thousands of individuals worldwide. Hundreds of individuals have responded in locations from Japan, Ghana, Brazil, Mexico, U.S. and other parts of the world showing her companionship and giving her thanks especially in difficult times all over the world. They are now jumping in the fasting bandwagon! Makeda Dread continues her mission of spreading love, positivity, health and the amalgamation and appreciation of all cultures.